Dear Reader.

If you are new here, welcome to my Substack. For the last few weeks, every Friday I’ve been publishing writing that may become excerpts from the book I’m working on “Glottis: Love Letter to the Open wound”.

This entry will not be like the other entries. It probably has nothing to do with the book.

It’s going to be about what I’m doing tomorrow. What the Philosopher, and the Carpenter (Uncle Surjan), and I, are doing tomorrow. We are putting the headstone, a “Stele” on Leo’s grave.

This week has felt heavy and complicated. I sense I am coming toward the end of this phase of the grieving. I feel there are just a few more posts left in this series. After which this substack will transform into something else. Hopefully something lighter. But today there are 6 different unfinished posts in my drafts folder and I’m not quite ready to let go of any of them. I have learned my lesson about pushing creative projects into the world before they or I are ready.

I made myself a promise when I was in hospital with Leo fighting for her life. When I thought the foreseeable future would be filled with the most extreme varieties of care work. I decided that, if events unfolded in such a way as to allow me to continue making art, I would put aside my former pride in things always needing to be perfect and coherent. That I would share “shamelessly and often”. So today I’ll share some images, a few words about milk, graves, and a poem I wrote the day of Leo’s funeral.

If you want to read excerpts from the book, or you are the kind of person who wants things to make sense, you may want to go back to the beginning.

Thanks for being here…

Tomorrow is the day we put Leo’s “Stele” in the ground of her gravesite. It’s the end of a long line of bureaucratic, practical and physical tasks that delineate the creation and ending of a human life. I did not know what a “Stele” was before we decided to use one. Just in case you also have no idea what it is, I’ll now explain what I learned about them:

A “Stele” is a column. Like a plinth. The kind that might hold up a Greek monument, or adorn a grave site of a stone-age princess. It’s a fairly common word in German to describe a grave marker that is taller than it is wide. In English, the same word applies but mostly for describing ancient monuments. “Stele” is also a biological term, where it has quite a different meaning:

In a vascular plant, the stele is the central part of the root or stem[1] containing the tissues derived from the procambium. These include vascular tissue, in some cases ground tissue (pith) and a pericycle, which, if present, defines the outermost boundary of the stele. Outside the stele lies the endodermis, which is the innermost cell layer of the cortex. (Wikipedia)

Like everything else in Germany it was not totally straight forward to get permission for our Stele. There is an application process. Diagrams and stamps, fees and approvals must be passed through. The bureaucracy of death is vivid as life.

Leo’s Stele is made of oak. The shape that touches the surface of the ground is square rather than rectangular. By definition, it reaches towards the sky.

After I gave birth the doctors offered me pills to “stop the milk from coming in”. When I asked what was in them and what they would do to me, they explained they were “dopamine blockers”. They would prevent those “happy” hormones from heralding lactation.

I couldn’t imagine what worse suffering I could put myself through, in those hours immediately after pushing Leo’s corpse out of me, than to prevent my body from feeling whatever positivity it could muster. Natural chemical relief. I declined.

My milk came in.

“Embodied practice is structured by knowledge in the form of technique, which is made up of countless specific answers to the question: what can a body do?... technique is knowledge that structures practice.” (Spatz, 2015, p.1)

Three days after the birth my breasts had swollen to a hideous size. Ever the technique fetishist, I tested out a wide a variety of “engorgement reduction methodologies”. I drank sage and peppermint tea by the liter, wore a tight fitting bra at all times, and expressed a little milk when I had to. The rest of the time I covered my breasts with ice packs. I found these weird crescent-shaped packs, open at one end, with holes for my nipples. Designed exactly for the purpose of cooling the over-hot production of breast milk. Though they were comically small for my enormous tits. I was so numb I accidentally left an icepack on for hours without its cover. It left a months-long moon of freezer burn. The philosopher and I tried to lighten the mood one day by covering ourselves in green clay - to take the heat out.

I realize that the Philosopher comes off rather badly through all this writing. It doesn’t fit my “Glottis” narrative to spend time talking about all the reasons I loved him so much, or why I thought he was going to be a wonderful father to our children. What I’m about to say does not in any sense absolve him of the monumental degree to which he fucked up. But it also should be said, somewhere, at some point, that he is not the one dimensional hapless idiot he might seem from reading this text. I’ve never seen a human being try so hard. Amongst all the darkness there was a surprising amount of light. That was something he worked to let in. When he was with me, he was trying his best. Sometimes pushing himself to the point where his best devolved into utter malfunction. Making everything worse. We have that in common.

It feels strange to be sharing this in such bare language. But it is Friday. I promised myself I would share what I was creating, fearlessly, once a week. And this week, rather than coming up with a painstakingly crafted document connecting all the threads of knowledge I acquired from this trauma, what I’ve been working on is moving on. Making necessary monuments to loss, so I can let go. Part of that is taking the time to express the milk of my rage. I need to let my anger go alongside my grief.

There are two physical monuments to Leo. At separate ends of the earth.

The cemetery “Georgen Parochial 1” we will visit tomorrow. It is very old. Centuries of corpses and ancient tombs rest there at the border of Friedrichshain and Prenzlauerberg. Right now the flowers bloom so brilliant you’d thing the whole of Spring was concentrated inside its stone walls

Then there is the “Aszodi family monument”, at my Dad’s farm in the Strezlecki ranges (in regional Victoria, Australia). At Christmas time my father, brother and I planted a flowering gumtree over Leo’s ashes. On a hilltop with a spectacular view. Dad built a comically large fence around the tiny sapling. More recently he has been constructing a kind of rock garden to surround the tree. You can see him here working with his big green tractor. Assembling rocks so we can sit and contemplate as she grows.

The Stele that will rest on Leo’s cemetery grave is a joint production between the Philosopher and our friend the carpenter, “Uncle Surjan”. They made it together. The father planed the oak, and chose the directions of the grain. With the left over bits of wood he cut from the larger body, he made “Bauklötze” (children’s building blocks). Which he gave to the daughter of a friend on the occasion of her third birthday.

The steel and concrete foundations of the Stele will sit in the earth. Just separate enough from the wood to prevent it getting damp and rotten. While being solid and deep enough for the Stele to stand strong for decades. These foundations are an invisible though essential part of the construction.

I think most people bury their dead without getting to know much about this process. I feel lucky to say the hands that planed and shaped and poured over Leo’s monuments were family. Her “Handwerk” made of love.

I have no skill with steel or wood. At her funeral I contributed bodily fluid. Her flesh of my flesh, in ash, my tears and milk, months ago went in.

Tomorrow, when we lay the concrete foundations. They will have a glittering secret. Though there is no way to tell for sure, I suspect they will be the only such foundations amongst the rows of somber monuments. Uncle Surjan mixed the concrete fundaments lovingly with “gold”.

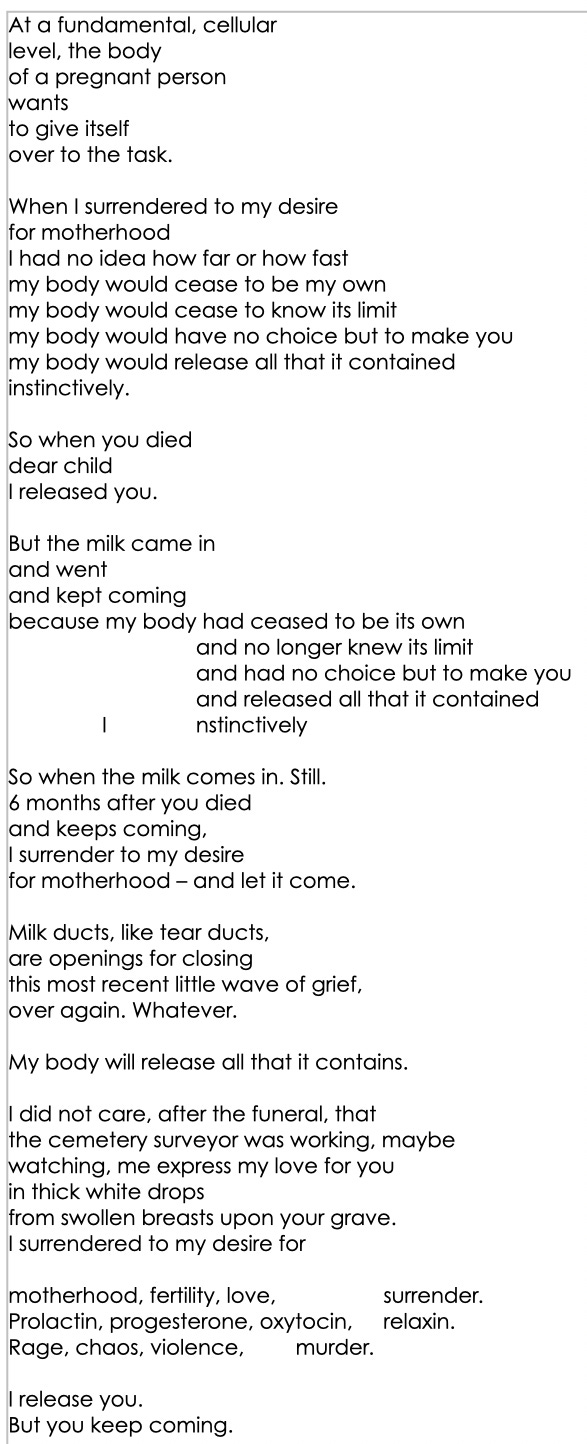

Milk Poem:

Tomorrow at 11am we “finish” the grave. There will be no more paper, no more stone, no more earth to move on this earth for her life. We have disposed of the baby clothes. The high chair. Moved back into separate apartments. Separate lives. I no longer feel the echos of my pregnant belly in the angles of my vertebrae. After tomorrow, there will be no more physical reminders of our obligations to the state.

but Still. There is milk. Every now and then, from my sagging, wrinkled breast: a single pearl-white tear.